Journal of Law, Information and Science

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Journal of Law, Information and Science |

|

LIU HUA[* ] & XIAO HONG-RONG[**]

On the basis of a theoretical demonstration of a legal system’s utility, this paper makes an overall evaluation of the dynamic utility of China’s patent system since its establishment. The proof analysis shows that there is a connection between the utility of a patent system and the degree to which China has developed: there is a close correlation between the number of patent grants and the GDP of a nation. In addition, utility models and designs have had a remarkable impact on China’s economic growth, while the impact of inventions has been limited. The authors suggest that the present emphasis on the perfection of China’s patent system and other relevant policies should be shifted towards innovative high technology. It is also essential to improve the commercial environment in which patent technology is utilised.

Evaluation of the performance of a legal system is a fundamental method by which to examine, create or select the rationality of the system. A descriptive analysis, however, will provide only a superficial understanding of the relationship between the legal system and its utility and overall effectiveness. Proof analysis, on the contrary, is an effective way to study the performance of systems that overcomes the drawbacks of traditional qualitative analyses. It makes the study as accurate and quantitative as possible. Since those factors can be treated as analytical variables, the executive course of systems becomes transparent. It should be noted that a legal system analysis is not merely a mathematical problem, and quantitative analyses must be combined with qualitative analyses. Following these ideas, the authors make an appraisal of the dynamic utility of China’s patent system so as to uncover the problems that have occurred during its executive course. The authors then suggest some measures to improve the system and government administration.

The most straightforward approach to measuring the dynamic utility of a legal system is to evaluate the actual effects and functions of that system. The Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property referred to the protection of patent rights for the first time as early as in 1883, and clearly stated that industrial property rights were to be protected.[1] The Patent system has been in practice for over a hundred years. The WTO affirmed the purpose of the patent system in 1995 in the Agreement on Trade–Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs): ‘The protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights should contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare, and to a balance of rights and obligations.’[2] From the above statement, we notice an apparent change in the purposes of the patent system, from the pure protection of individual rights to the balancing of the protection of individual rights with a regard for the broader public interest. The balance between individual interests and public interests has become the axis of the patent system. This shift in emphasis is also reflected in China’s patent law: ‘This law is enacted to protect invention-creations, to encourage invention-creation, to foster the spreading and application of invention-creations, and to promote the development and innovation of science and technology, for meeting the needs of the construction of the socialist modernisation.’[3]

The examination of the dynamic utility of the patent system can be divided into two issues from two different perspectives. Firstly, in terms of individual rights, whether a patent system can protect the interests of patent right holders so that intellectual labour can be rewarded and innovations encouraged.

Secondly, in terms of social interests, whether a patent system can provide an unimpeded channel for scientific and technological advances and the dispersion of innovations, and whether a patent system can elevate a nation’s productivity and increase its DNP per capita. The nation’s economic development is the supreme objective of the patent system.[4]

1.1 As early as the 19th century, when the patent system was initiated, the debate concerning the first issue had already begun. Philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill believed that the establishment of the patent system was a positive development. They argued that the patent system provided a shelter for private rights of intellectual property, and that it was efficient to define intellectual property as private property because it encouraged inventions and creations. Their view is widely accepted by many scholars today. The opposing view holds that a patent system has no positive influence on the quantity of inventions. F. Taussig and A.C. Pigou argued that invention was a spontaneous activity of human beings, and that the practice of protecting patents had no relation to the numerical increase of inventions. Somewhat similarly, K. Arrow suggested that intellectual property is public property with zero marginal cost. The personalisation of intellectual assets will result in increasing marginal cost and hence the reduction of the application and dispersion of inventions. Such a view derived from Arrow’s concentration on the marginal cost of patent application. It is aimed at saving total social cost but ignored trading costs arising from the commercialisation of inventions, which is the foundation of such property patent rights. In history, some western countries (for example, Holland), which once abolished patent law according to the above theory in the 19th century, restored it in the 20th century. This illustrates that the third opinion had already been overtaken by history. The second opinion mentioned above has its historical background. There are indeed numerous inventions that have no direct connection with markets. They probably arise from personal inspiration or non-profit pursuit. However, in highly developed market economies, the intellectual property system enables all the patent holders to gain considerable recompense. It is an indispensable means by which to stimulate innovation.

Posner by this means suggests that legal protection of property rights was justified because the law was able to realise efficient utilisation of various resources.[5] In essence, the patent system is a system of interests. Although the system itself does not create interests, and its function is merely to select and identify the interest relationships among people involved in innovations, it is the patent system that makes it feasible to utilise inventors’ intelligence more efficiently, through the interests relationship/legal relationship established by national authority. The overall efficiency of innovations is hence improved. The classical objective of the interrelationship between property rights and efficiency is to improve overall economic efficiency through the effective utilisation of limited resources on the basis of property rights protection. It contributes to economic growth and accelerates innovation.[6] The establishment of the patent system and the general system of intellectual property systematised private rights.[7]

However, the contribution of the patent system is more extensive. Because the advantage of private rights is in their internality, the objective of private decisions on resources utilisation is to maximise personal profits. At the same time, the personal assumption of the costs forces owners of private property to consider carefully when they are making decisions. Therefore, compared with the public property and national property systems of greater externality, the patent system, as a private property system, is a more effective incentive mechanism. ‘Intellectual property is a private right.’[8 ]The WTO not only reconfirms a fact that has been admitted in many countries’ laws long ago, but also demonstrates its commitment to the establishment of intellectual property law within the world trade system.

1.2 The second part of the utility inspection is focused on the economic effects of the patent system. As a code of behaviours, law is a product of society as well as of economy. The political and the legal systems of a country restrain its economic freedom and individual conduct, and also affect its economic utility.

The following economic analyses demonstrate the positive effects of the patent system on economic growth.

The patent system provides an impetus to innovation. More profitable investment opportunities than traditional technological industries arise. The capital output ratio grows and marginal profits increase progressively. As a result, economic activities achieve long-term continuing growth by breaking through short-term confinement. The patent system thus has a progressive effect on marginal profits derived from innovation.

The costs of innovation include Research and Development (R&D), licensing agreements, technology dispersion and innovation applications. R&D costs are fixed costs of the early phase and have no relevance to the number of licensees and the production scale of licensed technology. However, the costs of technology, trade, dispersion and application do have an impact upon the number of licences and the production scale. They change in the same direction and constitute the liquid costs. Because the fixed costs of innovation do not vary with production output, the same technology can be used repeatedly, and because the scale of technology utilisation and the number of users are not restricted in theory, the costs of R&D remain unchanged in spite of overproduction. Such quality of R&D costs causes the long-term marginal cost of innovation progressively to decline. This provides innovators with an internal economic motive during the course of conversion from innovative technology into actual productivity. It is particularly appealing to business firms in pursuit of maximum profits. Business firms are the nucleus of innovative activity in many countries where patent systems are established. Successful firms possess more patent rights than ordinary ones and thus possess the core competitiveness to gain comparative advantage. Various recompenses for firms’ innovation input are guaranteed by the patent system and constitute the main part of the increased amount of GDP.

On the basis of theoretical analyses of the utility of the patent system, figures incapable of direct comparison can be converted into comparable ones. In this way, a proof analysis is feasible. It is internationally accepted to use GDP as the measurement of a nation’s economic growth. Moreover, the number of patent applications and grants in a nation can be used as an adequate measurement of the nation’s patent system. Although other indicators are available, a proof analysis is preferred because it offers vast and complete data. In a qualitative analysis, ordinary statistical methods will suffice if the pattern is clear and the data not complex. The fewer materials available, the more complex statistical methods required. Here, the correlation analysis approach of regression analysis is applied to the examination of the utility of China’s patent system. It should be noted that the data concerned with Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan are not included in the following analysis because their patent laws differ from those of Mainland China.

Table 1: Quantity of patent applications & grants & GDP in China from 1985 to 2001

|

Year

|

Applications

|

Grants

|

GDP

(100 million yuan)

|

|

1985

|

14372

|

138

|

8964.4

|

|

1986

|

18509

|

3024

|

10202.2

|

|

1987

|

26077

|

6811

|

11962.5

|

|

1988

|

34011

|

11947

|

14928.3

|

|

1989

|

32905

|

17129

|

16909.2

|

|

1990

|

41469

|

22588

|

18547.9

|

|

1991

|

50040

|

24616

|

21617.8

|

|

1992

|

67135

|

31475

|

26638.1

|

|

1993

|

77276

|

62127

|

34634.4

|

|

1994

|

77735

|

43297

|

46759.4

|

|

1995

|

83045

|

45064

|

58478.1

|

|

1996

|

102735

|

43781

|

67884.6

|

|

1997

|

114208

|

50996

|

74462.6

|

|

1998

|

121989

|

67889

|

78345.2

|

|

1999

|

134239

|

100156

|

81910.9

|

|

2000

|

170682

|

105345

|

89404.0

|

|

2001

|

203582

|

114252

|

95933.0

|

Source: State Intellectual Property office of PRC, Yearbook of Patent Statistics 1985-2000.

Website of National Statistic Bureau: www.stats.gov.cn/sjjw/ydsj/

It can be seen from Table 1 that the number of patent applications and grants has been rising at a rate of 17.9% per annum since 1985, the year the patent system was initiated in China. It shows that the patent system has had a noticeable effect in encouraging innovation. This reflects the public confidence in the legal authority of the patent system.

The number of patent applications and the number of patent grants both peaked in 1993. That is a positive reaction to the first revision of China’s patent system in 1992 when China included ‘medicines, chemical reagents’, ‘food, beverage and flavouring’ and ‘micro-organism’ in its patent protection. In that revision, the authority of patented methods was extended to products directly acquired according to those methods, import authority was added to the patent law, and the term of protection was also lengthened. As a result, the power to protect patents was strengthened remarkably. It is a good illustration of the correlation between the perfection condition and utility of a system.

There are also some pleasant changes in the composition of Chinese domestic patent applications. There was a sharp increase in 2000, up 62.5% compared with the previous year, and up 3.9% in proportion to the total number of domestic patent applications in the previous year. Such a remarkable increase is a reflection of a higher level of overall science and technology. The number of firms’ patents for invention made up 63.4% of the total domestic contemporary applications. Moreover, the figure in 2000 increased by 138.3% compared with the previous year, and increased 7.4% in proportion to the total number of firms’ applications in the previous year.[9] Business firms, as the main source of technological innovations, have evidently increased their awareness of patents.

As for the correlation between the patent system and economic growth, a statistical report on industrial intellectual property undertaken by the World Organisation of Intellectual Property in 1985 indicated that the top ten countries in the world in terms of the quantity of patent applications had corresponding industrial levels. Q. Todd Dickson has undertaken a quantitative analysis comparing the number of patent grants and the GDP of 92 countries. He found that there was a positive correlation between the two.[10] Developed countries lead the world in the quantity and quality of automated intellectual property; similarly, their levels of technology and economic growth are pre-eminent. Is this conclusion,[11] however, applicable to other regions and economies? Is it applicable to China, where a patent system has existed for only a short period of time but whose economy is growing rapidly?

The analysis of China’s patent system is divided into two phases. In the first phase, a microscopic chronological analysis is used to determine whether the patent system can consistently promote China’s economy. In the second phase, a multi-spot horizontal structural analysis is undertaken to discover positive factors of China’s patent law which enhance economic growth.

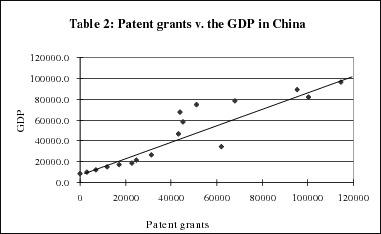

Table 1 provides the number of China’s patent grants and the GDP from 1985 to 2001. The approach of Regression Analysis is applied to test the correlation between the two groups of variables.

The correlation coefficient of the above seventeen pairs of sample values is described as r.

When r>o, each pair of the variables is in a positive correlation;

when r <o, each pair of the variables is in a negative correlation.

There is always | r |_1, that is, | r | approaches 1 when y (GDP) is in significant linear correlation with x (the number of patent grants). If the linear correlation between x and y is insignificant or it is completely non-linear, |r| approaches 0. According to the data in Table 1,

r=0.917135149

This is an ideal linear correlation coefficient. When the confidence level is assumed to be 99%, the critical value r0=0.632, then r>r0. Each pair of the sample values is closely correlated. According to the above calculation results and the original data in Table 1, we can draw the conclusion that the number of patent grants has a significant correlation with the GDP in China.

We may further work out the linear regression equation of y (GDP) and x (the number of patent grants):

y=0.82266656x + 8728.036658.

Accordingly, it can be concluded that the larger the number of patent grants, the greater contribution patent grants can make to Chinese economic growth. For every increased patent grant, there is a corresponding 0.82 unit increase in GDP. The Patent system continues to have a positive effect on the Chinese economy.

Different types of innovations have different degrees of influence on economic growth. Innovations for which patents are granted fall into three categories, utility models, design patents and patents for invention. Utility models reflect a firm’s ability to make technical innovations; design patents illustrate the firm’s ability to make market innovations; and patents for invention denote the firm’s ability to make product innovations.

Let us choose the quantity of patents for invention, utility models and design patents in 31 autonomous provinces in 1996 to form three data columns: {xi1}, {xi2}, {xi3}; and choose the GDP of various districts to form the data column {yi}; i= 1, 2, 3,…31. Then we have (xi1, yi ), (xi2, yi), (xi3, yi), representing the three pairs of sample values of the three kinds of patents and the GDP of China. By testing the correlation of three columns, we have:

The correlation coefficient between patent for invention and GDP: r1=0.3937463

The correlation coefficient between utility model and GDP: r2=0.7198289

The correlation coefficient between design patent and GDP: r3=0.6690497

In the same way, we may work out the following correlation coefficients from 1997 to 2000.

Table 3 : Patent grants v GDP of Chinese districts

|

|

1996

|

1997

|

1998

|

1999

|

2000

|

2001

|

Critical value

|

Analysis

|

|

Inventions v. GDP

|

0.3937*

|

0.379438*

|

0.351932*

|

0.3507732*

|

0.3909688*

|

0.4249077*

|

0.355

|

?

|

|

Utility models v. GDP

|

0.7198#

|

0.774068#

|

0.8306167#

|

0.8687695#

|

0.9101229#

|

0.9028956#

|

0.456

|

r >r0

|

|

Designs v. GDP

|

0.669#

|

0.669821#

|

0.669461#

|

0.6921936#

|

0.7067047#

|

0.685138#

|

0.456

|

r >r0

|

Note: *confidence level =95%, #confidence level =99%

The above data indicates that the quantities of patent grants for inventions, utility models and design are all in positive correlation with the GDP in China. In addition, the utility model has the closest correlation with the GDP. This trend is increasing. The correlation between design patents and the GDP is also quite close, but stable. Patents for invention have the weakest correlation with GDP and the trend is in decline.

The results of calculation and tests further confirm the promotional impact of technological innovations on the economy. But different types of innovations have different degrees of influence on economic growth. The close correlation between utility models, designs and GDP testifies that those two types of innovative technology make much bigger contributions to economic growth than inventions. As noted above, utility models reflect a firm’s ability to make technical innovations; design patents illustrate the firm’s ability to make market innovations; and patents for invention denote the firm’s ability to make product innovations. In order to gain a competitive advantage in markets, Chinese enterprises rely predominantly on the improvement of technology and the renewal of designs. They are generally weak in product innovation. The proportion of the three types of patents in China is a good illustration of the problem. Even in 2000, although the proportion of patents for invention was the largest one of the three, it was no more than 12% of the total. There was a noticeable gap between China and some other developed countries.[12]

Certain conclusions can be drawn from the above theoretical and proof analyses.

3.1 The patent system has been in practice in industrial countries for hundreds of years. In a developing country such as China the patent system, though established only for a short period of time, has also proven effective.

3.2 The Patent system, as well as the subjects it protects, requires regular innovation. With social economic growth and technological progress, the prompt adjustment and perfection of the patent system will have an effect on the utility of regimes. Innovative technology, the subject protected by patent law, is an extremely important element.

Patent law is thus different from other laws. Its emergence and application is bound to affect the division of social benefits. Therefore, patent law and related intellectual property law must be revised in accordance with new interest relationships. It is also essential to enrich the content of patent rights, to increase the number of subjects under protection and to carry out more protective measures. As a result, the legal relationships within patent law change faster than those of other civil laws, and the stability of patent law is relatively weaker than other laws. Society should show tolerance and adapt itself to this feature of the patent system. It is the cost that we have to bear if we wish to enjoy the benefits of the system.

3.3 Not all countries provide protection for utility models in their patent law. However, such protection exists in China. The result has been satisfactory. Such practice is in correspondence with China’s overall level of innovation at present. However, the emergence of utility models and design patents demonstrate the delicate and fickle nature of innovation. People rely upon short-term and rapid return to achieve growth, but lack enthusiasm and patience in time-consuming and vast-input inventions. Market failure as well as system failure exists in the process of innovation. Government administration can play a role in this case by providing a rational structure for a national innovation system – strengthening its support for fundamental research and high-tech growth so as to solve those problems that markets and the patent system cannot overcome.

In addition, the authority of government agencies over intellectual property is one of the characteristics that distinguishes the intellectual property system from other property systems. Government has the duty to adjust the protection level of patent law for various subjects and to use inspection mechanisms to improve the structure of patent technology and ensure the benefits of technology on economic growth.

3.4 Patent technology is a kind of marginal technology with potential market value. The Patent system provides an incentive mechanism to maximise output of technological innovations. However, maximum output does not necessarily mean maximum profits. The spread and application of technological patents is a crucial step if the patent system is to stimulate economic growth. There is a noticeable phenomenon in the statistical analysis: with patent grants increasing in China, their correlation with GDP is declining. The phenomenon indicates that the rate of a patent’s conversion is not promising. Research show that in some countries (for example, Japan), the dispersion of technology has made more contribution to economic growth than has R&D. Therefore, regulations and regimes should focus on enhancing the production of innovative technology and the distribution of technology at the same time. Otherwise, the patent system will lack utility. Nevertheless, the conversion from patents to productivity cannot be completed solely through patent law. It is a comprehensive problem, which requires input from entrepreneurs, input from risk funds, orderly market competitions and standardised government administration. In general, all facets of society may play a role in the performance and development of the patent system, in addition to courts and intellectual property authorities of all levels.

In conclusion, we should adopt a rational attitude towards the growth of China’s patent system.

[*] Liu Hua, doctoral candidate, School of Management, Huazhong University of Science & Technology; Associate Professor of Law, Central China Normal University. She has been engaged in lecturing and research in Intellectual Property Law. Correspondence address: Law School, Centre China Normal University, PRC, 430079. Email: lhccnu@hotmail.com

[**] Xiao Hong-rong, Lecturer in Economy School, Central China Normal University.

[1] Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property, Article 1, clause 1.

[2] International Agreement on Trade related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (‘TRIPs’), Annex 1B to the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organisation, opened for signature 15 April 1994, [1995] ATS No 8 (entered into force 1 January 1995). Article 7.

[3] Patent Law of the People's Republic of China, Chapter 1 General Provision, Article 1.

[4] Liu Maoling, Economic Analysis on Intellectual Property Law, Publishing House of Law, 1997, p 6.

[5] Richard Posner, Economic Analysis of Law, Boston: Little, Brown and Company. 3rd edition, 1986.p 30.

[6] Liu Chuntian, Intellectual Property Law, High Education Publishing House, 2000, p 19.

[7] Wu Handong, Intellectual Property Law in the Coordination Mechanism of Science, Economy & Law, Law Study, 6th issue, 2001, p 133.

[8] TRIPs, preface.

[9] Wang Jingchuan, ‘On the Implement of the “Three Representatives” in order to Create a New Situation of Patent Work in the New Century,’ Vol.12, No.67, 2002, p 4.

[10] Q.Todd Dickinson, ‘The Relationship Between the Protection of Intellectual Property and Economic Development in The 21st Century,’ International Symposium on the Protection of Intellectual Property for The 21st Century, Beijing, PRC, October.28-30, 1998.

[11] Wu Handong, ‘Intellectual Property Law in the Coordination Mechanism of Science, Economy & Law,’ Law Study, 6th issue, 2001, p144.

[12] Website of Japan Patent Office: www.ipdl.jpo.go.jp/

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlLawInfoSci/2001/17.html